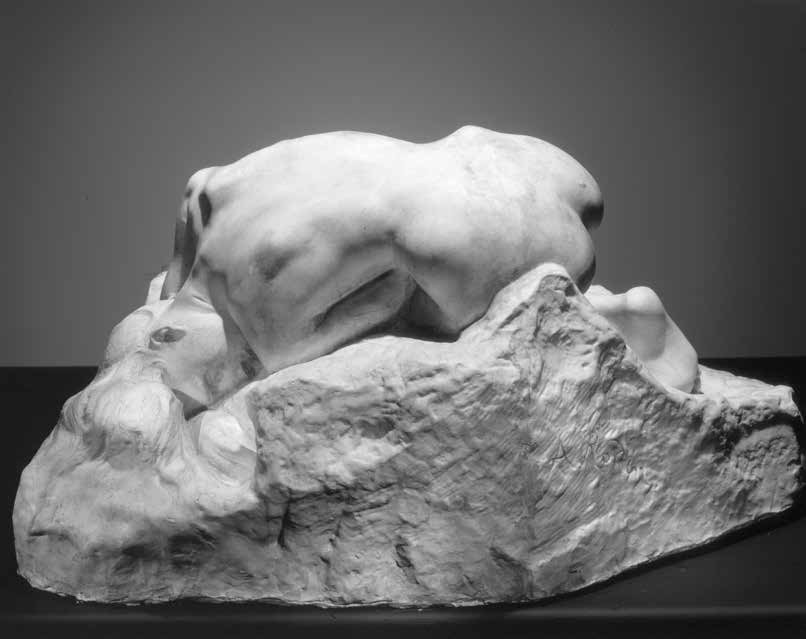

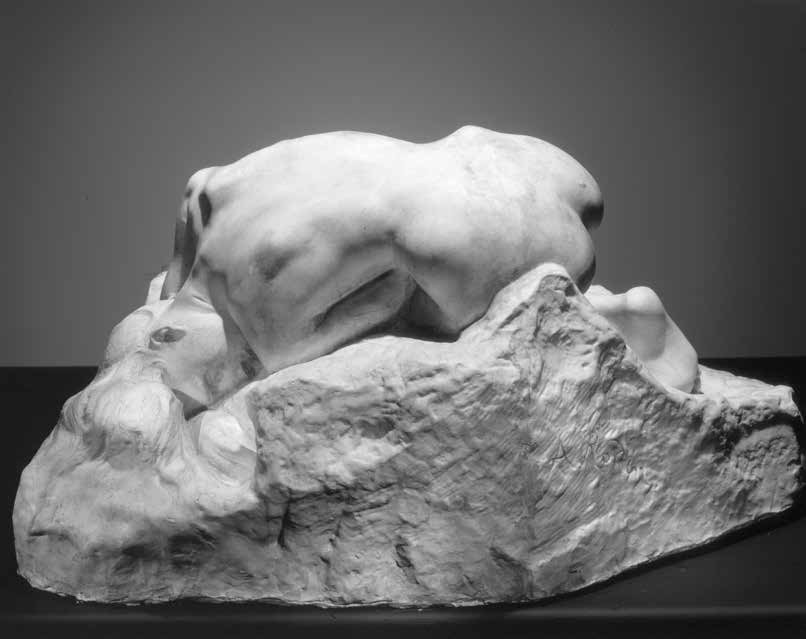

Auguste Rodin, The Danaid, Foundry Plaster.

A David v. Goliath battle has been quietly playing itself out in the French courts for the last 17 years in the curious case of Auguste Rodin’s posthumous bronze casts and the right to produce, exhibit and sell them.

As is the case with all art-related disputes, this is primarily about money (Musée Rodin generates an income from the production and sale of its bronzes).

Take one wealthy collector, a state-owned museum, and the rights to the work of the most recognized sculpture artist of modern times, and you end up with a fully fledged nuclear war in the rarefied world of high art.

The story began when American-born Gary Snell, a prolific collector of Deco-style art, was approached by an art dealer with an offer to acquire a few of Rodin’s foundry plasters. Realising the potential, Snell joined forces with a Liechtenstein entity, Gruppo Mondiale, to produce a very limited series of bronzes,

In order to understand the significance of this offer, we need to digress some and explain to the reader what “foundry plaster” means.

Auguste Rodin created most of his works first out of clay. The clay was kept moist until he was happy with it, after which he would instruct a mold maker to prepare a mold known as a moule à bon-creux. The very first plaster from the moule a bon creux is referred to as the “original plaster”. The moule à bon-creux, or the “negative”, would be destroyed after use (the few remaining ones have deteriorated over time). The positive form was sent to the foundry to have it cast in bronze and is henceforth referred to as “the foundry plaster” (the foundry plasters are made from a new mould, itself made from the original plaster). Alexis Rudier’s foundry was Rodin’s principal foundry and has, therefore, the best link to the artist.

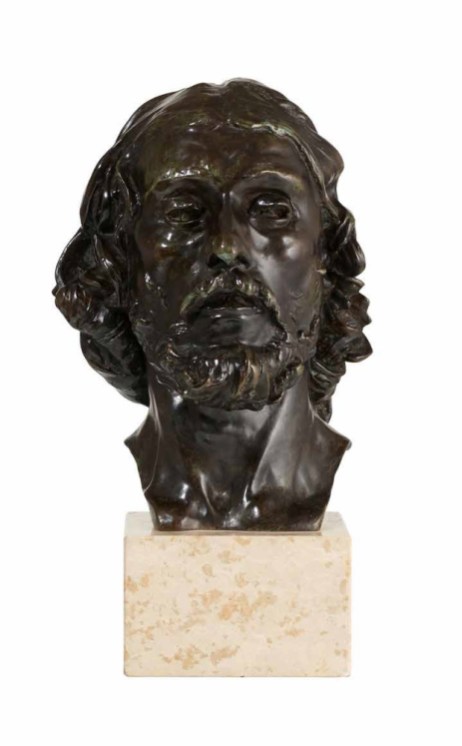

Auguste Rodin, The Head of St. John the Baptist (1879), Bronze .

Rodin Intellectual Property: A Seemingly Straightforward Application of the Berne Convention

At the end of the 1960s the definition of an original work of art was enshrined in a law (Article 98A, Appendix III, formerly Article 71, of the General Tax Code) which provides that “Are considered as works of art […] limited edition print carvings limited to eight copies and controlled by the artist or his successors […]”. This regulation means that a sculpture is considered as an original work of art so long as it is limited to 8 copies.

Thus, Musée Rodin had the right to produce only 8 copies that are considered “original bronzes”; all further casts being “posthumous bronzes”.

The Parisian institution was founded in 1919 as part of a condition in Rodin’s will that granted the French State ownership of his collected works. Under French law, and in line with the near-universally adopted Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, the right to enforce copyright expires 70 years after an artist’s death. Thus, in 1987, 70 years after Rodin’s death, the museum were no longer able to enforce the copyright that had been bequeathed to them.

After ’87, all of the artist’s works reverted to the public domain with the exception of the Moral right (the right to be identified as the creator of the work and to object to any distortion which would be prejudicial to the artist’s reputation). Musée Rodin holds this “moral right” and so has cast a number of unchallenged posthumous bronzes, many of which are sold at auction with a tag price to match. A recent auction saw an original posthumous Rodin bronze, Penseur, Petit Modele, sell for $2,775,505.

Snell, it has to be pointed out, is obsessive about researching and documenting detail. He established that the plasters he was offered had been acquired, for the most part by a single collector, directly from George Rudier, the former foundry owner’s nephew who had taken over in 1954.

The Art Collector interviewed Gary Snell who elaborates on his initial interaction with Musée Rodin and the chronology of the subsequent dispute:

“Once I understood the significance of the foundry plasters, I went to Musée Rodin and asked them to authenticate them. The museum confirmed that they were indeed foundry plasters from the Rudier foundry.

“Word spread that I was buying Rodin plasters and in the early 90’s, when the IP rights fell back into the public domain, everyone who had something to sell would approach me.

“I would approach Musée Rodin to similarly authenticate everything unless I bought it from Christie’s or Sotheby’s.”

Snell spent 5 years researching the casting technique used by Rodin’s foundry for the production of the bronzes. He then found an Italian foundry that was able and willing to replicate this technique in a minute detail, including the complex and onerous patina process. Each bronze, he says, takes 3 months to cast and refine.

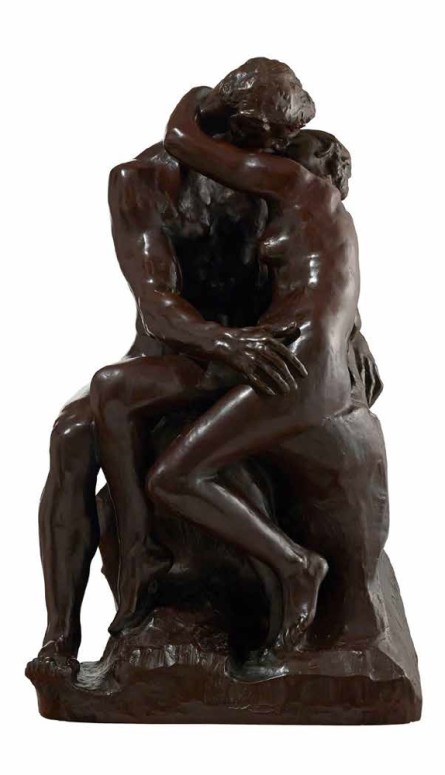

Auguste Rodin, The Kiss (1885), Bronze .

“To begin with, I bought the plasters for my personal collection only, however, I soon started getting offers to exhibit the bronzes at museums around the world.

“My relationship with Musée Rodin at the beginning was amicable and I had regular exchanges with their former archivist, Alain Beausire, as well as the then museum director.”

In fact, Beausire endorses the Snell plasters quite unequivocally, in written articles on the subject, notably in a Le Journal Francais piece.

“When I told them of my intention of producing a limited edition of bronzes for the purpose of exhibiting and selling them, they raised no objection.”

The Musée Rodin itself does, of course, also exhibit posthumous Rodin bronzes, as do a number of reputable institutions around the world, namely the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, the Cantor Arts Center at the prestigious Stanford University, The Glenbow Museum in Calgary, the National Gallery in Berlin, The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

The main difference is that Musée Rodin also sells these bronzes in order to fund itself.

—-

Art War: Musée Rodin vs. Gary Snell Becomes a Case Study of Tit-for-Tat Legal Wrangling

The relatively cosy relationship Snell enjoyed with the Musée Rodin ended abruptly in 2001 when the Royal Ontario Museum staged an exhibition of his bronzes.

“The then ROM curator decided to draw attention to the event by suggesting our exhibition of Rodin bronzes rivalled in quality the Musée Rodin bronzes.”

This assertion spurred the Musée Rodin into action and a flurry of articles appeared in the main Canadian newspapers at the time, setting the ”line in the sand” of the conflict in the making.

The following statement appears in the Globe and Mail in 2001:

While critics — including the Musée Rodin in Paris, the executors of the Rodin estate — have not denied that the pieces are foundry plasters, they have argued that they were made 40 or 50 years after Rodin’s death and should be regarded as, variously, counterfeit, “too far removed from Rodin’s hand,” or unauthorized reproductions.Globe and Mail, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/rom-extends-rodin-exhibition/article4158259/

The Musée Rodin followed on by starting a lawsuit against Snell alleging counterfeiting and citing a criminal action filed against Snell by the French State. Bizarrely, the State didn’t pursue the action nor were Snell’s lawyers able to access the court file.

Incensed, Snell instructed a legal team to file his own action against the French State in 2007 – for dysfunction of the public service of justice.

By 2014 Snell, along with Gruppo Mondiale, a Liechtenstein-based company partnered with Snell’s company Euro Group, appear to have prevailed: the French court delivered a judgment that the French State had no jurisdiction over the Snell bronzes and that French law was therefore not applicable.

Given that the Musée Rodin had previously documented both the provenance and worth of bronzes, Snell argues that,

“Musée Rodin alleged that the bronzes were counterfeit simply because they had not authorised them, in what is, essentially a commercial dispute.”

Things turned more sinister in 2016, when the Appellate Court simply overturned the previous judgment and found that the French Court did, in fact, have jurisdiction, and that French law was applicable, after all – in spite of the already established facts.

At this stage of the hostilities Musée Rodin appear to have taken a new tack, now insisting that the moulds were French and therefore the bronzes were subject to a particular French customs tax code that is only applicable in France.

Snell is adamant that neither he nor the Italian foundry ever used any moulds from France, nor cast any bronzes in the country which renders the point moot. In any case, he asserts quite logically, the relevant French customs tax code is only applicable in France.

“The court case has gone through the full gamut of challenges touching upon international and French intellectual property law, and the very particular French droit moral [moral right] law. We have used foundry plasters and original production techniques and given the bronzes proper attribution, so the droit moral should not be an issue either.

“Ultimately, this has the hallmark of a commercial dispute over the right to exploit works in the public domain and to protect the income stream of Musée Rodin.”

As far as Snell is concerned, the attempt to apply a French tax law outside of France is motivated by Musée Rodin’s “determination to retain a monopoly on selling posthumous Rodin casts and protect their profit margin”.

The state-owned Rodin Museum is, of course, able to protract litigation ad infinitum. Snell, on the other hand, has to continue funding his own representation and has been doing so since 2001.

The strategy of obliterating an opponent through years of legal wrangling is hardly new, even if the ethics of it are questionable. Stay tuned for the last act in the French State v. Snell saga as we report on it early 2019.

Meantime, the Snell collection of Rudier plasters and posthumous bronzes is a unique and remarkable one, given the plasters’ undisputed provenance and the legal right to reproduce the works, just as Musée Rodin and its other illustrious counterparts in other countries do.

Auguste Rodin, The Danaid (1885-1886), Bronze.

The Rodin Collection is available exclusively via The Art Collector. Please e-mail us for further information (marketing @ theartcollector.org).

Saving...

Saving...