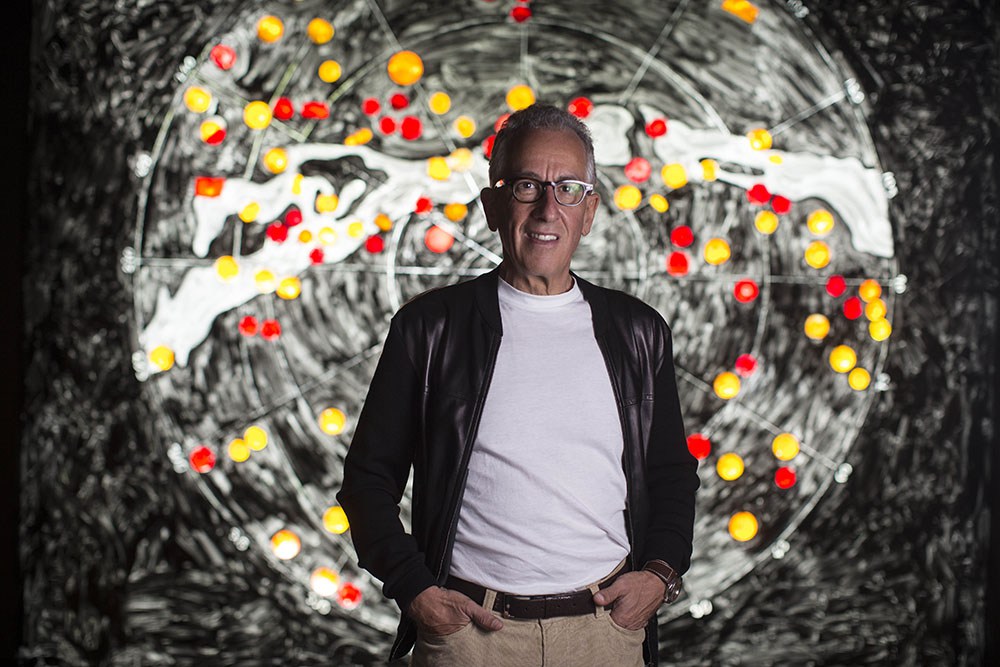

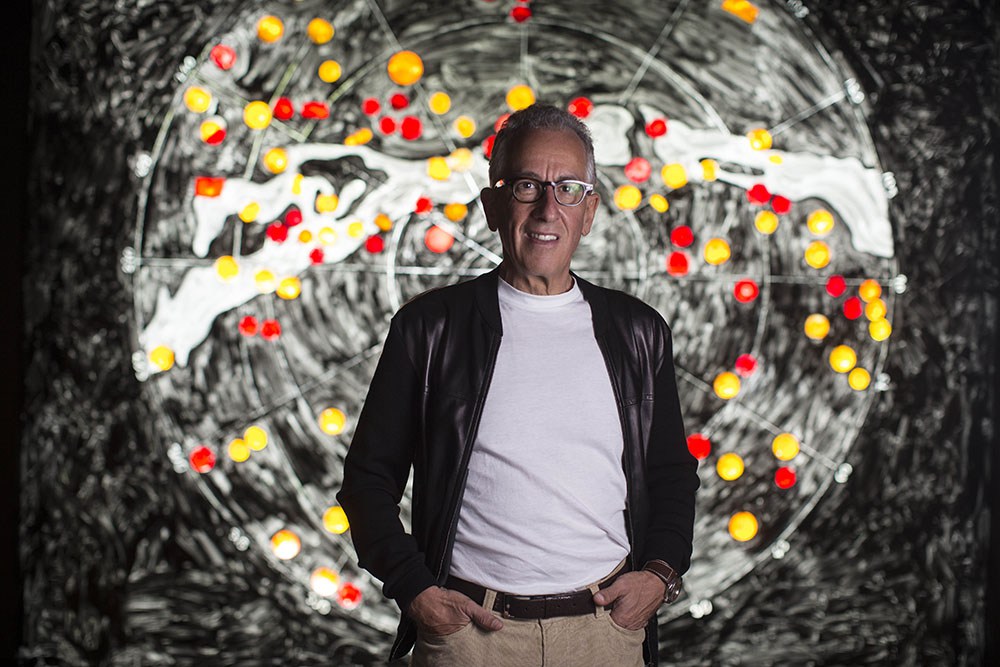

Most philanthropists are complex personalities. Their drive, motivation, foibles and often circuitous road to bequeathing inherited or self-made wealth make for a fascinating study.

Few are ostensibly dichotomous in the way Simon Mordant is.

A chartered accountant with a passion for art; a money man who wants to give it all away; a public-school educated Brit who rejects the British class system; a home counties native who chose to forsake Blighty for Oz.

The apparent dichotomy is likely lost on him because he has a ready and supremely well-articulated rationale for each of the above.

The narrative may have been smoothed through repetition but the story is no less astonishing for that.

Simon was just seven when he was sent to boarding school. Even in 1960s Britain, this would have been considered very young and, while he doesn’t dwell on it, he concedes that it was a “tough environment”. There are well-oiled arguments both for and against the practice, with proponents arguing that building a spirit of independence and a stiff upper lip warrant the loss of family life. Certainly, young Simon was determined to prove to his parents, and to himself, that he could crack it.

There was little by way of art at boarding school where he shared a dorm. The head of the arts department was an influential figure, nonetheless, and encouraged his interest in the subject. At seventeen, Simon bought his first work of art; a drawing from the Royal Academy summer show.

Rather than just hang it on the wall, he took the somewhat unusual step of writing to the artist to ask what had inspired the work.

He attached the written response to the back of the drawing, which remains part of his collection to this day.

So Simon, the budding art collector preceded Simon, the accountant.

The gap year travel is a well-established rite of passage for well-to-do English school leavers.

Simon had never been out of Europe so he decided to see ho far he could go in a year, travelling overland, on his own, through Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan.

Arriving in Sydney was life-changing. He recounts it matter-of-factly now but the connection with Australia at the time must have been profound and spiritually liberating. The sense of achievement getting there, enhanced by the hard-wired and easy-going egalitarianism of Australians, underscored the fact that ability does, can, and should trump privilege.

A fervent and practising believer in meritocracy was born there and then.

And then, there was the LIGHT…

At the start of our conversation, I quote back to him one of his own lines: ‘In the UK, I fear that the grey environment might have dampened my creative expression.’

The quality of light in Australia needs to be experienced as it doesn’t quite lend itself to description but, for all I know, he may have meant the above metaphorically, as well as literally. The English class system can be quite stifling for the inquisitive spirit and creative of mind.

Simon Mordant did, of course, return to the UK. For one thing, he had committed to complete his education and for another, he could only settle in Australia if he had a profession qualification.

He returned to Australia several times before finally making the continent his home and by the time he did, he already had countless friends, “a new family” there, and a full support system.

His corporate path is well documented. He has been a part of the investment banking world for decades and co-owns one of the most respected corporate adviser firms in Australasia. Luminis Partners has an exclusive strategic partnership with the global NYSE listed advisory firm Evercore and specialists in strategy, M&A, takeovers, conflict resolution, acquisitions and capital market activities, working with major corporation, governments and institutions.

His journey to place Australia prominently and firmly on the art and culture map of the world is equally well-documented and ties in both with his passion for art and creativity, and with his personal conviction that a man should do all he can to “make a difference in the world during his lifetime.”

The journey started with the realisation that there was no institution dedicated to contemporary art in Australia.

Mordant was fortunate to meet an Australian woman with whom he shares his philosophy of life. He and his wife Catriona, a former ballet costume maker, are one of the most prominent donors to the arts on the continent and beyond.

It was a pledge of $5m from them, along with a like pledge by David Coe, that kickstarted the campaign to re-develop the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney.

Today, Mordant is a Chairman of the Board of the MCA Australia, a director of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, a director of MOMA PS1 in New York, a Trustee of the American Academy in Rome, a member of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a member of the Executive Committee of the Tate International Council, a director of the Garvan Research Foundation, a member of the Wharton Executive Board for Asia, a member of the Advisory Board of Venetian Heritage in Italy, and a Chair of Lendlease’s Art Advisory Panel for Barangaroo. He was Australian Commissioner for the 2013 and 2015 editions of the Venice Biennale.

I ask him if he might have chosen a creative career had he not become a chartered accountant. He gives me an answer that he has given in previous interviews: that he is creative in business. It’s something that goes without saying: how else could he be as successful as he is?

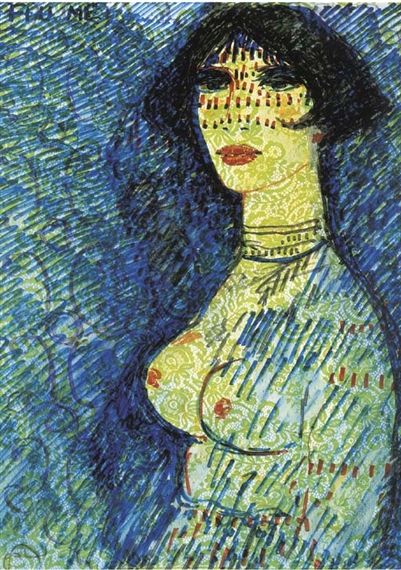

BBeyond is more intrigued by the mindset of the collector, so I ask what it is that he collects and why.

He and his wife are a 95% match when it comes to their taste in art, he says, which is lucky for them.

A shared taste in art, music and humour are the prerequisite for a good and enduring marriage, and a partnership of minds such as theirs.

Like most collectors who are deeply involved in selecting works for their collection (as opposed to investing in contemporary art), he says he enjoys the engagement aspect.

“You can engage with contemporary artists whereas, much as you might admire Van Gogh, you cannot ask him about his works.”

The Mordants collect what they love and have supported certain artists for decades. They never sell.

As their tastes evolve, the have begun to donate works they no longer feel they want to keep to institutions. This makes them the ideal ticket for an emerging artist or any artist, in fact, as the value of the works never suffer.

Mordant is only too aware of the challenges facing emerging artists. A primary dealer who nurtures them and advocates for them is vital, he says, and young galleries do a wonderful job in this respect.

Great galleries, on the other hand, don’t do enough. Their museum-quality spaces could and ought to be used for showing emerging artists during the slow summer period. Mordant says.

I wonder aloud if this is ever likely to happen and he replies, quite rightly, that it only would with consensus between, and pressure from, collectors.

I also wonder on the subject of philanthropy – why not cancer research or the environment or another culture-related cause even?

Mordant’s answer is not that different from other philanthropists’, but is delivered elegantly and without missing a beat, in his pleasantly controlled, articulate and still British accent after more than 3 decades of living in his adopted country.

He says that he has a “limited ability to engage with other forms of art” (other than the visual and performing arts that is) and that, anyway, you can spread yourself too thinly if you try to support too many causes.

One needs to make a difference in an area one is passionate about and support it meaningfully, well beyond the financial contribution.

He has done so, without a doubt. When Australia got its much and long-lobbied-for opportunity to redevelop it temporary pavilion in Venice, Mordant and his wife seized on the challenge and relished the opportunity to do something of legacy proportions for Australia, personally donating to, and spearheading the fundraising campaign to build a new permanent pavilion.

Is he motivated by leaving a legacy or a desire for immortality?

He says that he isn’t. Rather, he believes in “making the world a better place while we are alive – and having a lot of fun doing it”.

The Australian pavilion in Venice is the first 21st century building there. It it a remarkable landmark of contemporary architecture by Denton Corker Marshall, the winner among six shortlisted architects.

I ask Mordant what he is most proud of and, without hesitation, he says “of my wife and my son”.

His son, photographer Angus Mordant, is a successful photojournalist in NYC and he is well aware of his father’s views on the subject of inheritance.

Mordant senior is frequently quoted as a staunch opponent to giving one’s children anything other than the fullest support and encouragement a parent can give.

“Inherited wealth,” Simon says, “is destructive”. It robs one of ambition and drive, and feeds into the class system he so abhors.

Beyond that, he takes well-deserved pride in being something of a global ambassador for Australian art. He was instrumental in forging a partnership between MCA and the Tate for the latter to purchase Australian artists’ works, but his frequent references to Australian culture point to a far deeper engagement.

There was, he knows, a perception of Australians as being generally uncultured, certainly at the time he first emigrated there (his own father declared his son’s education had been wasted, only to change his views in later life).

This perception has been subtly changed over time, thanks to men and women like him. He has certainly been, and remains to this day, one of the country’s most passionate advocates.

Reflecting on our conversation later, it occurs to me that the chosen name for his company, Luminis, has a deeper significance than just the straight translation, “full of light”.

The extraordinary light that he was so struck by on arriving in Australia is something that he has now, in a way, inverted: reflecting it back to shine on the continent and its unique, distinctive culture.

Challenging public perception, and then changing it on a global scale, all in one’s own lifetime, is certainly something to be proud of.

Content exclusive to The Art Collector and BBeyond Magazine.

Saving...

Saving...