Adding a robust cultural dimension to the French Riviera, in the pretty village of Mougins, is Christian Levett’s Musee d’Art Classique. Given that it’s only existed since 2011, the museum has garnered a remarkable number of accolades and recognition from the notoriously uppity art community. It is the only French museum to be nominated for the 2013 European museum of the year award and has also shared the 2012 Ken d’Or 2012 award for best museum with the Louvre. In 2011 it won the Apollo Magazine ‘New Museum of the Year’ award.

Levett is by all accounts a very prolific, even addictive collector, but it is not simply the size and diversity of his collection that attract attention – it is the unique juxtaposition he has created between antiquities and art. The rationale of exhibiting Greek Corinthian helmets or Roman busts next to a distinctly contemporary work is what defines not just the museum itself, but Levett’s philosophy of collecting and of displaying his collection.

This rationale has been the subject of countless column inches and is best delivered verbatim by the man himself in a Q&A interview below.

As ever, The Art Collector is fascinated by and focuses on the collector as much as the collection itself.

Levett, in common with other serious art buyers, has a finance background which has enabled him to invest in what he is clearly passionate about. At the same time, he has acquired judiciously, identifying the antiquities class on auction catalogues as undervalued. This has also allowed him to indulge a self-avowed penchant for classical objects and owns the largest private collection of ancient armour in the world, as well as a world class collection of ancient sculpture and bronze works.

He has also bought classically inspired works by ‘blue-chip’ artists such as Rubens, Matisse, Chagall, Picasso, Cézanne, Calder, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Lautrec, Hirst and others he considers eminently able to withstand both the test of time and art market fluctuations.

And while his collection is not just investment-led (he is knowledgeable, eloquent and very obviously emotionally attached to it), the museum is vocational rather than business or a vanity project, although access to the museum is ticketed.

Levett has accumulated a small but similarly solid, recession-proof portfolio of investments. Listed on the back of his business card are a collection of ultra-high-end Courchevel chalets, two leading restaurants in Mougins, an archaeology magazine, a niche fashion label and a gluten-free confectionary brand.

He is an active partner in the Vigo Art Gallery in Mayfair, London, together with Toby Clarke.

Having retired from managing other people’s money and focusing instead on his personal interests, he has also developed a strong philanthropic focus.

Levett is a major sponsor of The Ashmolean Museum, The British school at Rome, The British Museum, The Royal Academy, the National Gallery and The Soane Museum. He has sponsored an ancient armour day at UCL and is sponsoring an ancient sculpture day there, as well as a ‘Classical meets Contemporary Art’ day at Kings College London.

He has also financed archaeological digs at Naucratis in Egypt and Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli alongside the British Museum, as well as a dig at Maryport Roman Fort on Hadrian’s Wall.

He has funded classics courses at Wolfson College, Oxford, where he is an Honorary Fellow, and sponsored one of the Egyptian galleries at The Ashmolean Museum where he is also a Fellow and on the board of trustees. He loans artworks routinely to other museums and exhibitions, both from his museum and his personal collections. He has been involved with sponsoring exhibitions at the Royal Academy, such as the Bronze Exhibition in 2012, the Ai Wei Wei exhibition in 2015 and the current Abstract Expressionist Exhibition.

TAC: How did you get involved with the Vigo gallery?

CL: I got into Vigo because I’d bought a several art works from Toby Clarke who set up the Fine Arts Society’s contemporary department ten years prior. I back it financially while he runs the business. We are both involved to some degree, but he does 99% of the work and also chooses the artists we sign up. He always asks for my opinion on the artists so there is some of my input there. My primary function, however, is to help make sure the gallery runs as a successful business and to co-ordinate on what we’re buying, whether for stock or trading.

TAC: How do you decide which artists are bankable?

CL: I normally defer to Toby on the basis that he can see something that’s completely new and cutting edge and in sync with what the market is looking for in terms of current trends, much better than I can where contemporary art is concerned. Even if it’s not an artist I would personally collect, we tend to agree where the gallery is concerned. Some artists have been absolute no-brainers: Ibrahim El Salahi and Masaaki Yamada, the latter who’s works we showed at the Frieze Masters this year and the former we will be showing at Art Basel Miami in December. These are highly established 20th-21st century artists, though we also represent artists such as Kadar Brock and Leo Drew who are more up and coming and yet already being looked at, or purchased by, museums. Toby finds them generally; some of them he’s known for years, such as Marcus Harvey, a major YBA artist. Ibrahim, on the other hand, had never really had a major art gallery support him before, despite Tate Modern billing him as the ‘Picasso of Africa’ during his exhibition there three years ago, so in a market that’s absolutely dying for established African and Middle Eastern artists, he was a fantastic find by Toby. Ibrahim has been making artworks since the 1950s and set up an art school in Khartoum in the 1960s and while he’s late 20th century rather than early to mid 20th century, he’s about as close to the Picasso of Africa as one could get.

TAC: When and what did you first start collecting?

CL: I am a manic collector. I started collecting coins and First and Second World War campaign medals when I was about 7 or 8 and caught the collecting bug then. They were very cheap, so I bought them with my pocket money. In my 20s I started collecting art works to decorate the house. Then I got into collecting coins again – Roman coins – and late 18th century and early 19th century hand-painted natural history books (I just found them really beautiful). I then went mad on collecting antiquities for years, to the point where I was stacking them up in storage. The museum in Mougins was born in 2009 when I bought a large medieval building, but it took two years to turn it into a museum. Mougins was a Roman settlement and the centre of the town dates back to the 11th century. This building itself dates back to the 14th century and was originally the village prison, turned into a mill probably in the 18th or early 19th century because Mougins was the major hillside for growing flowers for Grasse, the perfumery centre of Europe that still produces perfumes for the major design houses. In the 1950s the building was turned into a house and any pre-existing features were completely removed, so when I bought it, it was easy to just strip it out again and turn it into four floors gallery space.

As the years went on I started collecting modern and contemporary art, invested in the Vigo gallery and retired from commodity trading, my job for the last 25 years, this summer. I am a trustee of the Ashmolean museum at Oxford and can hopefully have some positive input there.

Now that I have a bit more time on my hands, I’d like to visit a large number of museums and archaeological sites around the world that haven’t had time for until now. I often help out museums with raising money or I often help finance exhibitions myself.

At this point in my life, I love to travel around the world and enjoy the art market, turning what has been a hobby and a fixation for years into a lifestyle – and that’s aided with Vigo doing so well on the contemporary art side of things.

TAC: What are the rationale and narrative behind showcasing antiquities alongside contemporary works?

CL: In the process of buying antiquities, I would flick through art catalogues and notice art works with classical themes. We have at the Mougins Museum anything from oil paintings by Rubens of Vitellius and Vespasian as well as a drawing of a sphinx by Rubens, a huge bronze by Orazzio Albrizzi of Marcus Aurelius dating from around 1630 and paintings by Alessandro Turchi from the same period, all the way through to Damien Hirst’s Happy Head spin-painted skull that he did for an installation in the British Museum about seven years ago. Marc Quinn’s marble headed statue of Bill Walters sits on a white marble Roman-style pedestal alongside original ancient roman busts.

You can see in a very tangible way how the artists have been influenced by or had classical periods, or had an interest in doing a collaboration with a classical museum. Damian Hirst, Marc Quinn, Grayson Perry and Antony Gormley are a good case in point and the Mougins Museum contains works by all these artists.

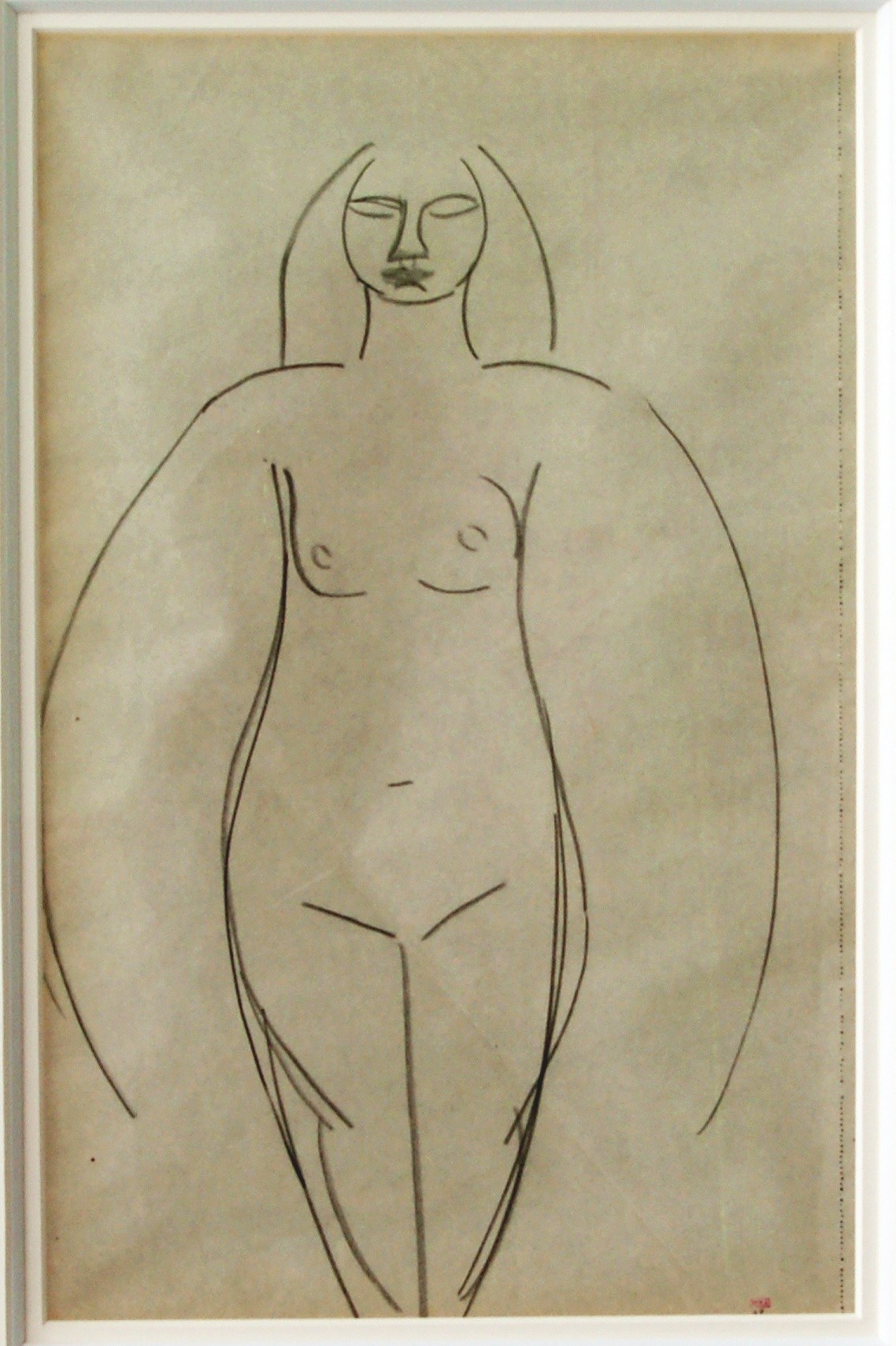

Picasso did a number of classical drawings in the 1930s; Yves Klein did a lot of classical pieces around the 1960s as did Dali; then the museum also contains Warhol Botticelli’s Venus, Chagall’s watercolour Bacchanalia, Jean Cocteau classical plates, a photograph from the 1930s by Man Ray of a Greek Corinthian helmet, works by Matisse and Egon Schiele and very many other artists you wouldn’t have imagined doing something classical.

Every time I saw something like this I thought: if I put a Man Ray photo behind a helmet at home, that’s going to be a really nice juxtaposition, or a Rubens painting of Vitellius next to a Roman bust of Vitellius that I bought, that would be an incredible synergy.

I felt that acquiring art works relating to classical themes would also make the museum more interesting and attractive to the public, and appeal to both those who are interested in art and those who are interested in antiquities. It’s easier to buy contemporary art than antiquities these days. I bought a lot of my antiquities in the early 2000s when the market was relatively quiet.

TAC: What are your views on provenance?

CL: I’ve always bought with the best ethics in mind where provenance is concerned – from major dealers and auctions houses – provenance is absolutely critical in the antiquities field in particular, though really in the entire art market too.

TAC: Do you not think that the new – when it sometimes references antiquity – is often a de-contextualized rehash of it?

CL: It can be forced a little sometimes, but when you look at the 20th century and before, not really. As an artist or academic, when you look at a Roman or Greek sculpture, you look at it first and foremost as an art work. But as a member of the public, and this applied to me before I got into the antiquities world in a serious way, you initially perceive them more as a piece of history. I was always fascinated by the history of the pieces – where did they come from, who used them, which villa they were in… – it conjures up all these emotions of wandering around Rome 2000 years ago in togas and spending silver coins in wine bars and going to see gladiators. But you don’t initially look at these things as works of art which they most certainly are, because someone sat in a workshop in the ancient world with a hammer and chisel and sculpted them as an artist.

People tend to initially look at the age before they see it as a work of art and that’s if they see it as an artwork at all. Whereas if you look at a 19th century sculpture, you would more likely perceive it as an art work rather than a piece of history. The same is true of contemporary pieces. In fact, there’s no difference between any of them in terms of being a work of art. So when modern artists look at ancient sculpture, they think: that’s the start of art and therefore, something that I should study and include in my body of work too. Artists creating sculptures go back several thousand years BC, and from 800BC sculpting and bronze working was becoming extremely refined.

By the time you get through to the later Roman period, artists were already mimicking Etruscan and Greek sculpture and bronze working that had gone hundreds of years before. Roman artists must have felt the need to experience that even earlier part of art history and do something that they felt was part of their development as an artist, part of their training and part of their raison d’être. It is both a homage to the past and part of their artistic and cultural DNA. Nothing has changed, artists operate the same today as they have for thousands of years.

TAC: Does contemporary art offer a new narrative?

CL: I think with contemporary art the challenge is to do something new. You could also argue that’s been the challenge for the last 300-400 years. Given that in the last 100 years art work hasn’t been about sculpting, painting or drawing something, it can be about a plain object or an idea – it’s really about coming up with something new, that’s the challenge. The idea of it has to be genius even if the execution of it isn’t genius. Prior to that, the execution had to be genius and the idea was often routine.

TAC: Do you think we’ll have a return to technical virtuosity? Shift away from the conceptual?

CL: Manzoni would say a book is an art work. There are plenty of amazing painters putting paint on canvas – Peter Doig is a good example of this as is Gerhard Richter. George Baselitz is another one. However, they still have to be doing something that’s cutting edge. Castellani, Fontana and Uecker are all great examples of this dating back to the 50’s. However, there’s no point in painting a nice portrait of someone or a nice landscape and trying to sell it commercially in the contemporary art space. This isn’t the 18th or 19th century. Victorian paintings are cheap for this reason, even though they can be the most exquisite art works. How many people are there in the world who can paint a beautiful portrait or landscape? There are 7.5 billion people on this Earth, so there might be a million people or half a million people who can paint brilliantly. So you’ve got to be doing something that’s different and after 200 years of trying already, from Turner to Impressionism, to Cubism, Surrealism, Zero Movement, to Pop Art, of course that then leads to the conceptual. In fact, conceptual art has already crossed over with most of these movements and has been around a very long time. Paint has been applied to canvas in so many different ways in the past 100 or so years that it’s getting harder to put paint on canvas and come up with something new, even though it does still happen.

TAC: What’s next, digital art?

CL: This is happening already; look at the recent Hockney show at the RA. Performance art, video art, the combination of all three with oil on canvas, all in the same art work now happens. I am not too sure how you can go beyond performance art or beyond Piero Manzoni seventy years ago saying that anything is a piece of art in itself. One may have thought that was the absolute ultimate and you couldn’t take it beyond that but lo and behold, we have. So the art world will keep developing, there’s no doubt about it.

TAC: What do you think is next?

CL: I don’t know. Throw a grenade into a room and shut the door and there you go, there’s a new art work? Call something a piece of social history, create a series of wine stains on a cloth an interactive piece of history and a piece of biological history in terms of whether you’ve made a mess of something and there you are…. dreaming stuff up as I sit here. You can come up with this kind of thing all the time. An art work doesn’t have to be shocking, which is a common misconception.

TAC: Which artist from the 21st century do you think will remain relevant? Antiques have withstood the test of time – are there any artists that will be relevant 50 years from now?

CL: Lots! Artists that sell for multi-million dollars rarely disappear off the face of the planet. Prices go up and down although over time they tend to go up. Generally speaking, the price of the well-known artist will always go up over the very long run. However, I would say that some of the American artists like Jeff Koons, Richard Prince and Christopher Wool which are selling works very regularly for $7m-$15m a pop, make artists like Castellani and Fontana look extraordinarily cheap and make Damien Hirst, Marc Quinn and Antony Gormley look like they’re being given away. Most of the YBAs trade for 300K or less with the exception of Damien Hirst but even with him; you have to go a long way to pay more than £2m. I think YBAs are very good value. There’s no doubt they’re here today and here tomorrow. Quinn and Hirst are extremely versatile artists besides.

If you’re buying blue-chip artworks by blue chip artists, then you’re going to do extremely well over time.

TAC: How do you make a blue-chip artist?

CL: A blue-chip artist is someone who has global recognition, who’s done major exhibitions around the world, who’s been collected by major museums and foundations, who’s been published many times and has an established group of professional collectors buy their works. Antony Gormley, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons are all household names. You could walk up to someone in the street, almost anywhere in the world, and they’d know who these artists are.

Artists selling for £20/30/40K, from galleries like Vigo, where they are going to be shown at major art fairs around the world, shown to major collectors and where the gallery is investing a lot of time and money into exhibiting their artists, also have a chance of becoming blue-chip at some point. This is not about a PR push, that term is badly used, and it’s not about creating something from nothing. You have to have a great artist to begin with as a gallery is only going to promote someone and spend money showing them around the world, if they really believe in them. If an artist is not in the major art fairs, they are not going to get recognition. Ditto if you’re not doing major exhibitions that museum people, big collectors and foundations attend. That artist is not being shown to the right people, in which case that artist should be trading at a decorative price of £5-£10k. It’s not a case of marketing someone and pumping them up, it’s a case of finding an amazing artist and investing in them. Is he doing something that potentially MOMA would have an interest in buying at some point? What is the art world looking for; will museums take this artist seriously? That’s how you have to think and this is not frivolous at all – it’s expensive.

TAC: Who’s the tastemaker – the client, the museum or the gallerist – or all of these?

TAC: Who’s the tastemaker – the client, the museum or the gallerist – or all of these?

CL: The artist has to come up with the ideas and execute them to start the process.

After that, the gallery is the intermediary conduit to the museum (usually albeit not always). Generally, galleries or dealers will find artists and try to discover one that could be potentially special. Ultimately though, it’s museums that will decide as it’s critical for an artist to be shown in museums to be a blue-chip here today, here tomorrow artist.

TAC: Do all collectors have an investment-geared approach?

CL: No, that’s the wrong reason to collect, unless you have a substantial collection which goes beyond decorating your home. Collecting is about having a passion for the things that you collect.

TAC: If you could have dinner with one artist, who would it be?

CL: Picasso, because he was versatile and trail-blazing and at the forefront of so many genres over such a long period of time. He is the grand master of 20th century art.

Saving...

Saving...