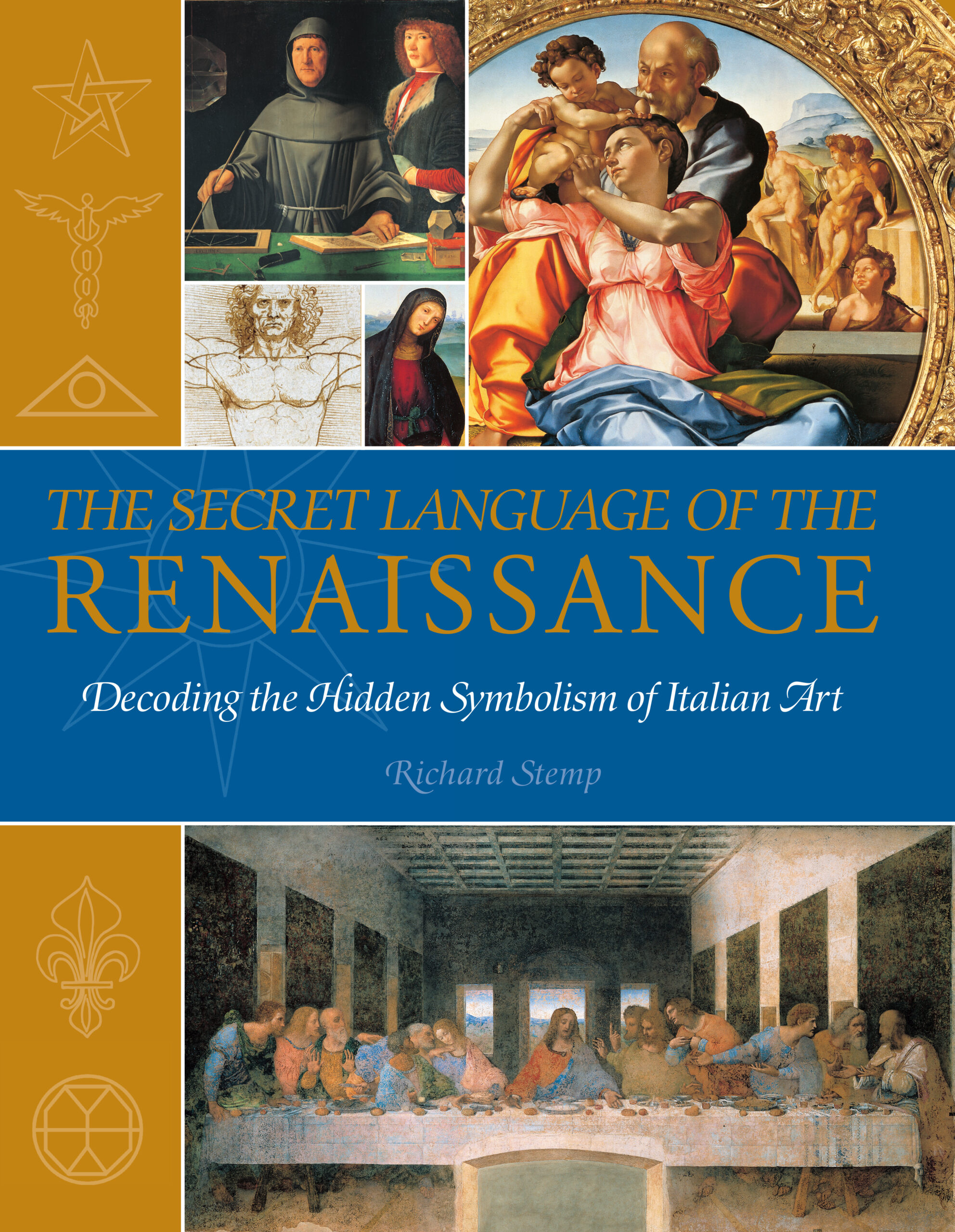

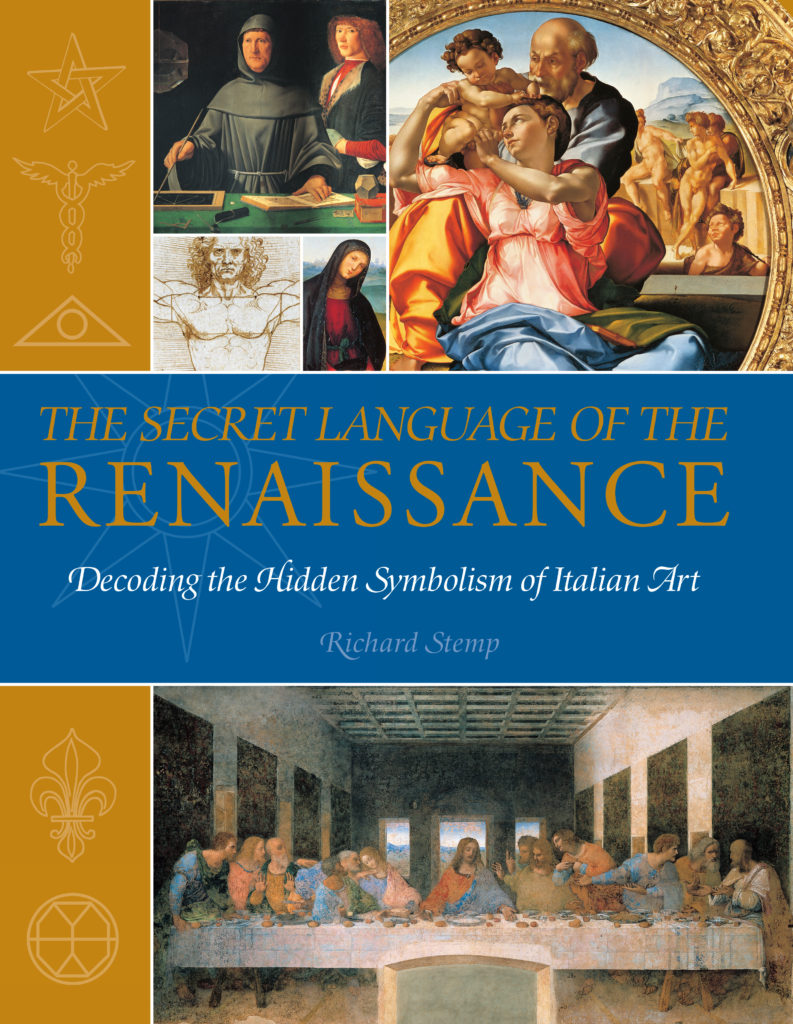

Ahead of the publication of The Secret Language of the Renaissance (July 2018), we asked author and Art Historian Richard Stemp Ph.D. about his new book.

Your book’s introduction opens with the lines: “The artistic splendours of the Renaissance are universally admired, but in the twenty-first century they are not always easy to understand.” If you had to summarise your book in a few sentences, how would you describe it and how do you address the issue above?

It is a general introduction to art and architecture in Italy during the Renaissance, but rather than getting bogged down in concepts and theories, or dragging through the artists’ biographies, I’ve tried to introduce the ideas expressed through Renaissance art in small, bite-sized pieces, so the book can be picked up, dipped into, or read from cover to cover depending on the tastes of the reader.

What kind of audience are you looking to reach with your new book, or is your aim for the book to be accessible to all (novices, art students, art historians etc.)?

It may be a bit of a cliché, but I would hope there’s something for everyone. For those with little or no knowledge of Italian art, I intend to start from the basics, and for those who know quite a bit, I suspect that some of those ‘basics’ would be a little surprising.

What are the the problems of over-attributing meaning retrospectively? Do you think this is a common issue?

I don’t think it is a big problem, to be honest. A few art historians get carried away with their line of thought, of course, and the odd crank thinks they can see 20th century-style diagrams of the brain in Micheangelo’s paintings. But the ideas in this book occur in enough other paintings and sculptures to be able to say that the interpretation is as close as we can get to the artists’ way of thinking. That’s not to say that many of the ideas are relatively new – though again, based on an established understanding of the renaissance way of thinking.

Do you see (m)any similarities from the art world in the Renaissance period with the contemporary market?

Not really. Most art during the renaissance was intended to communicate a particular idea, and not, as so much of the art market seems to be today, about a financial investment. If anything, the investment was in the afterlife. Whatever money was spent on creating these beautiful masterpieces, the intention very often was to please, or appease, a God who was very present in the belief of the owners of the art, and we can be all too cynical about this in the 21st Century.

If one accepts the idea of a Western art cannon (of which the Renaissance period plays a large role), do you think contemporary art will at some point become part of this rhetoric or do you think (in a vein similar to Arthur Danto) that this narrative has come to an end?

Whatever some theorists say, people will always want to put things into boxes, to classify them, and to decide what is good and what isn’t. Historians will always create narratives to explain the progress of events, of cultures, and of their visual records. Inevitably, therefore, art will also be moulded into different ‘cannons’, although what is seen as being important will always change with the constantly changing tastes of the times.

If you had to pick one artist from the Renaissance period to have dinner with, who would it be?

Donatello. I find his development, and later abandonment, of Renaissance ideals fascinating to the point of incredulity. What was going on in his mind when he abandon notions of proportion, form and idealisation in his late works, and how did he come up with the characterisation of some of his most famous figures, such as the bronze David, the interpretation of which, in all honesty, remains one of the unresolved secrets of the Renaissance. I’m not entirely sure his table manners would be that good though.

Dr. Richard Stemp studied Natural Sciences and History of Art at the University of Cambridge and has a Ph.D in Italian Renaissance sculpture. He works as a lecturer for the National Gallery, Tate, and Buckingham Palace, as well as on site in museums and churches across Italy for Art History Abroad. He has written and presented the TV series Art in the National Gallery and Tate Modern for Channel 4, and makes regular contributions to other programmes. He is also the author of The Secret Language of Churches & Cathedrals.

Saving...

Saving...