The Da Vinci exhibition has been hailed as the most significant and exciting exhibitions of the 21st century, to date. Tickets have never been sought for to such a large extent for a long time. Not even Placido Domingo’s performance earlier this year saw such an incredible international demand. But what is it, exactly, about Leonardo Da Vinci’s works which are so devastatingly attractive? TAC will endeavour to tell you the reason why you cannot miss this exhibit and why, if you have not done so already, you should buy tickets (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/leonardo-da-vinci-painter-at-the-court-of-milan/*/tab/1).

The Da Vinci exhibition has been hailed as the most significant and exciting exhibitions of the 21st century, to date. Tickets have never been sought for to such a large extent for a long time. Not even Placido Domingo’s performance earlier this year saw such an incredible international demand. But what is it, exactly, about Leonardo Da Vinci’s works which are so devastatingly attractive? TAC will endeavour to tell you the reason why you cannot miss this exhibit and why, if you have not done so already, you should buy tickets (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/leonardo-da-vinci-painter-at-the-court-of-milan/*/tab/1).

It is one thing to see a painting in all it’s glory; it is another to see the minute and complex process behind creating a masterpiece, such as Da Vinci’s are. Da Vinci is known foremost as a painter but also as a scientist and it is his mathematical precision in crafting figures wherein his genius lies; also the fact that his hand could wield a mighty pen and draw an even finer figure.

It is necessary to give praise to the National Gallery for the fantastic and thematic composition of the exhibit. However, in order to truly appreciate the works and avoid crowds, we suggest early morning or late evening for this exhibition as the unprecedented number of visitors is virtually unavoidable at midday.

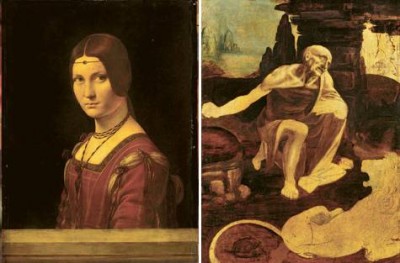

Da Vinci’s sketches may resemble those of his contemporaries. However, they contain a mathematical precision required for a realistic depiction which can be seen in many of his almost 3D-like portraits. We see Da Vinci’s scientific machinations in sketches such as ‘The ventricles of the brain, and the layers of the scalp’. Da Vinci’s dedication to proportion is only to be admired; it is clearly something which enabled him to create realistic (nay, perhaps surreal?) portraits of humans. We hint at a surreal aspect in his paintings as, in ‘La Belle Ferronière’ for example, we are almost separated merely by a frame; perhaps the sitter actually sits behind it. The portrait itself was apparently flattering to the sitter but it is dead accurate in its life-like quality and innate – and apparent – vitality.

Frequent visitors to the National Gallery would have already admired Leonardo’s ‘Virgin of the Rocks’, but, lo!and behold, suddenly there are two! However similar in theme and depiction, they are distinguishable. The one residing in London is more intense in colouring; yet we might say the one loaned us has a more intense emotion of the cherubs. The beauty which lies in Leonardo’s works are the captured expression, piercingly in depth and inspiring, but also his forms, enhanced by his technique of sfumato; this combination can be seen in his depiction of cherubs.

‘St. Jerome in the Wilderness’ sadly is unfinished. We can only try to imagine what the final version would have looked like. Yet to see the careful deliberation in the sketching of the figures gives us a hint at the skill required to perfect a form, and one which would accord to the saint’s expression. To fully appreciate this, the National Gallery put alongside this numerous sketches, or ‘Profiles of an old man’ to show the phases Leonardo went through to capture the correct expression; a holy but beautiful suffering. The repeated dedication commands admiration.

Few people have not heard of Da Vinci’s famous, ‘The Last Supper’. It would be futile to describe the impression one receives when seeing even a copy of this. Especially considering one’s response is subjective. One might consider booking the next flight to Milan to see the original, found in the Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Instead, we leave you with a quote by the man himself, Da Vinci, to contemplate:

There are three classes of people: those who see, those who see when they are shown, those who do not see.

Saving...

Saving...

1 Comment

Add YoursThank you for trying to explain the terminlogy towards the beginners!