It is not an everyday event to admire an exhibition of works in glass, this superb material whose colours hold light and all its fascination within it. Venice brightness weds the infinite colours of nature and just in Venice the stir spreads like an element from the mysterious throbbing of the lagoon. I am amazed at this plan for an exhibition, which will certainly be successful and arouse interest in this marvellous material, which surpasses even materials like bronze and stone. Glass has a soul and a tension, where poetry returns to us with the innovating pulsing of a new artistic life, worthy of the Most Serene Republic of Venice.” Umberto Mastroianni, July 1997

It is not an everyday event to admire an exhibition of works in glass, this superb material whose colours hold light and all its fascination within it. Venice brightness weds the infinite colours of nature and just in Venice the stir spreads like an element from the mysterious throbbing of the lagoon. I am amazed at this plan for an exhibition, which will certainly be successful and arouse interest in this marvellous material, which surpasses even materials like bronze and stone. Glass has a soul and a tension, where poetry returns to us with the innovating pulsing of a new artistic life, worthy of the Most Serene Republic of Venice.” Umberto Mastroianni, July 1997

The outstanding quality of glass is its brittleness and hence its contrast with strength, force or violence. Glass is precarious, provisional, always exposed to the catastrophe of breakage and hence irremediable destruction. Glass is frail, and needs to be treated with that delicacy of which it has always been considered an emblem, like something that at every moment is threatened with lethal danger.

The outstanding quality of glass is its brittleness and hence its contrast with strength, force or violence. Glass is precarious, provisional, always exposed to the catastrophe of breakage and hence irremediable destruction. Glass is frail, and needs to be treated with that delicacy of which it has always been considered an emblem, like something that at every moment is threatened with lethal danger.

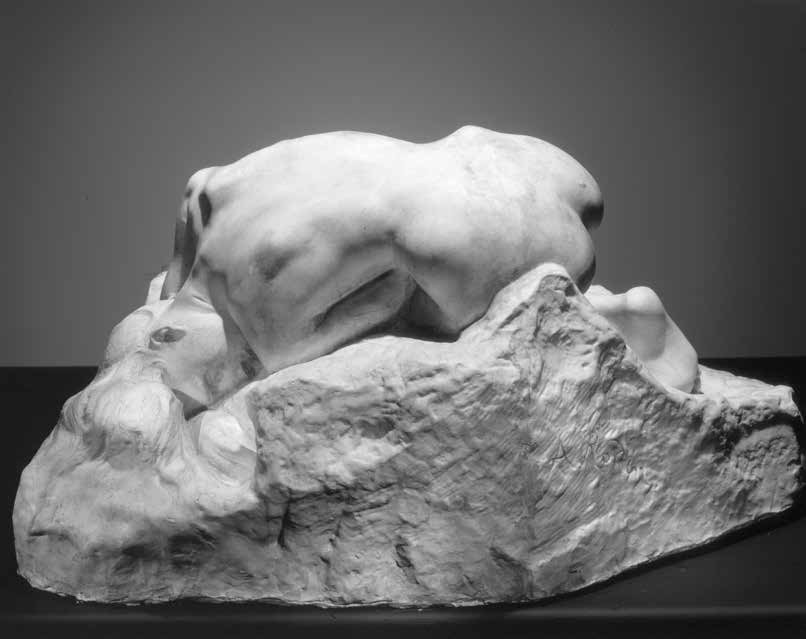

But for those who understand it, glass also encloses the mystery of its genesis in the glowing crucible, where fire liquefies it in the deafening noise of the flame. And in this way glass, by displaying its fragility, actually conceals the violence that gave it birth and that it still embodies, in a tangle of precariously balanced tensions. Glass both conceals but also represents a contradiction that stems from its material fragility, combined with the impetuous force which it then mysteriously embodies.  It is this contradiction that attracted Mastroianni the man, perhaps unconsciously, once the artist had made his choice. It is no accident that Mastroianni discovered glass only in old age when a man’s body, containing the strength of the spirit, dramatically confronts the body’s frailty.

It is this contradiction that attracted Mastroianni the man, perhaps unconsciously, once the artist had made his choice. It is no accident that Mastroianni discovered glass only in old age when a man’s body, containing the strength of the spirit, dramatically confronts the body’s frailty.

By its twofold significance of strength and fragility, glass expresses better than any other material the human contradiction of the body’s inadequacy compared with the spirit, and in a particular degree the violent conflict old age creates in us. Mastroianni did not renounce his strong and vigorous poetic, he continued to be himself, but transformed his mode of expressing himself: and he chose glass.

By its twofold significance of strength and fragility, glass expresses better than any other material the human contradiction of the body’s inadequacy compared with the spirit, and in a particular degree the violent conflict old age creates in us. Mastroianni did not renounce his strong and vigorous poetic, he continued to be himself, but transformed his mode of expressing himself: and he chose glass.

In this way he found himself faced with a singular evolution, unique like the whole of Mastroianni’s aesthetic and human experience, which took the form of an extraordinary artistic event.

“I haven’t even got time to die! I’m planning seven or eight years ahead! The Lord will make me die all the same, of course, and his will be done! But I want to way that this continuous decomposition, these ups and downs of images in me overlapped, are a terrible and wonderful thing. As an organism I was terribly conceived. I’m an explosion of life and I’m amazed…but the thing that surprises me most is that I don’t feel old”.

And in fact Mastroianni never did grow old, in the sense of the passions failing as the body wore out, the weakening of the will, the desire for peace as twilight falls. Mastroianni responded with passion and anger to the illness that was eroding his body and preventing him from continuing to respond, as he had always done, to the impulses of that unbroken will. His continuous exploration of the use of materials was the inner impulse that ld him to an almost sensuous use of glass, whose nobility as a prime essence he grasped, quite apart from the way it occurs and independent of (and opposition to) its importance in common use: this led Mastroianni to that “pioneering poly-materialism” which was one of the distinctive features of his art.

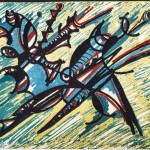

“Mastroianni seems to possess not just a feeling but a genius for materials: he reveals their force, their weight, their tension, texture, fibre, grain, warmth and splendour,. In reality the dominant motif of all his art is a tough, obstinate contestation of materials. This is evident above all in his reliefs, which at first seem made of various metals and glassy enamels, and then one realizes they are actually made of paper, cardboard and rags. One admires the artist’s extraordinary virtuosity, his baroque genius, his pioneering “poly-materialism” and one fails to realize that a material is not something that already exists but has been invented, created by the artist’s handling…”

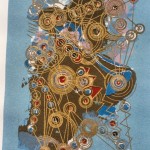

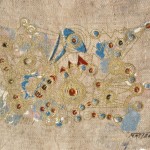

Mastroianni’s “poly-materialism” is an original magma, containing everything. He makes a selection  from it, and determines its presence, giving a direction to movement, depth to colour, and bringing out volumes and highlights. And it is precisely as a function of light and an element of its complexity that among the torn sacking, among the signs rapid as the darts of a creating Zeus, unexpectedly there emerges the glossy surface of bronze.

from it, and determines its presence, giving a direction to movement, depth to colour, and bringing out volumes and highlights. And it is precisely as a function of light and an element of its complexity that among the torn sacking, among the signs rapid as the darts of a creating Zeus, unexpectedly there emerges the glossy surface of bronze.

In this exploration and the quest for the expression of a concept-message (the emergence of life through the explosion of the earth’s surface) we could say that the jute sacking represents the formlessness but also the concrete materiality of being: the indiscriminate creation which as the first and fundamental attribute proclaims its own being. From this indistinctness (which is, all the same, and this involves us) there emerges the life revealed as living and hence distinct being, definitely self-affirmed, shining and splendid. This is the significance of first bronze and then glass, which emerge from the sacking, lacerating it as in childbirth.

In this exploration and the quest for the expression of a concept-message (the emergence of life through the explosion of the earth’s surface) we could say that the jute sacking represents the formlessness but also the concrete materiality of being: the indiscriminate creation which as the first and fundamental attribute proclaims its own being. From this indistinctness (which is, all the same, and this involves us) there emerges the life revealed as living and hence distinct being, definitely self-affirmed, shining and splendid. This is the significance of first bronze and then glass, which emerge from the sacking, lacerating it as in childbirth.

Calm, storm, calm: these are the phases of life, the seasons of history, the dimensions of the human vicissitudes that an artist, more than anyone else, lives through, and that he certainly expresses better than others. Recalling his youth, when his art represented “a certain neo-classicism, a certain realism,” Mastroianni added:

“When the war broke out, this marvellous movement was interrupted […] The events of life, of history, have perturbed me; I have had to realize what was happening, my sculpture was no longer capable of embodying that tragedy. I had to reinvent it and then I went on continually with these dramas, so it would be worthy of the experience we were going through; and I was always caught up in the need to renew myself endlessly.”

Mastroianni used glass because glass means light and light is a fundamental component of his poetic. The potent dynamism of his handling would be dumb if it was not invariably supported and enlivened by a skilful handling of light which bounds the fields and projects the lines to infinity, plumbs declivities, negating itself, and expands to cover broad planes. His first efforts of glass appear in the series of works in sacking, lacerated and in relief, of 1989-90 in which Mastroianni resumed his studies of the potential for extracting light from this one industrial material. Sacking is a challenge to light: its surface is naturally rough with interwoven fibres and further varied by the irregularities of the threads: though it captures the light in alternating shadows, it defines a “flattened volume” which the opaque texture further dulls. On this inert surface Mastroianni intervened with his passionate energy and traced his lines, immersed colours and finally reanimated the sacking by cutting and slashing it, creating reliefs. The sacking seems transformed and palpitates with the passion he infused in it. Exploiting the possibilities offered by Grassetti, Mastroianni inserted in these sacks, torn and in relief, points of force – points of light – created by inserting specially made glass. The encounter with this mythical material took place, its potential was grasped, and from that moment he undertook a new line of research into the fundamental theme of light.

Old age brought only one trouble and it was neither pain nor weariness: it was the limit that it set to the invincible will to be conscious and involved in life at every instant, capable of dominating it and bending it to his purpose. “We have to give a message to this indefinite world, which drowses and offends life. Boredom is the worst blasphemy.” Those who suffer from tedium are an offence to life.

For further details and information about the works being sold, please send us an email.

Saving...

Saving...