They say the life you live colours your sensibilities. Spending a lifetime collecting some of the greatest and most beautiful art objects ever created in the world must touch and shape one’s soul in a very unique way.

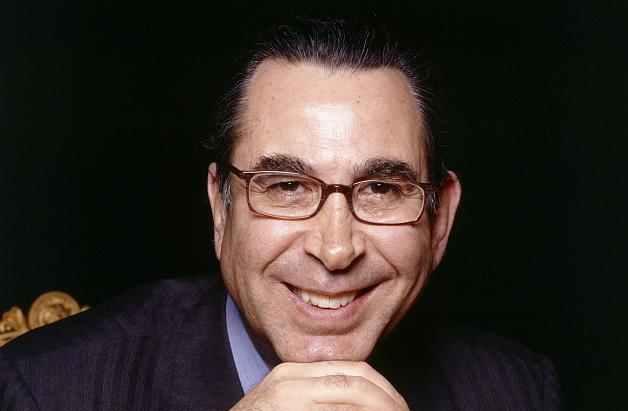

B Beyond and The Art Collector had the great privilege to talk to one of the most prolific collectors of all time, a humanitarian and interfaith ambassador, owner of the largest private collection of Islamic art, Nasser David Khalili.*

Professor Khalili has robust opinions and has earned the right to express them forthrightly because he is, quite simply, one of the world’s most important collectors.

He speaks more eloquently about Islamic art than any art editor or curator I’ve ever come across but it is his personality that most captivates the listener.

There are frequent flashes of generosity of spirit that cannot be scripted (we did not – nor do we ever – send questions ahead of the interview), nor credited to some cultural idiosyncrasy.

Like most great philanthropists, he is passionate but there is a certain timeless wisdom about him too.**

We salute him for his work with the Maimonides Foundation.***

As for his collection, different parts of which are frequently exhibited around the globe, it is one of the best-documented in the world, in a series of volumes published by the Khalili Family Trust. To appreciate its extraordinary beauty, its breadth, its depth, and the singular dedication with which it has been built, you need to experience it.

Q. Have you considered collecting from Islamic countries that don’t have an established art market or value?

DK: The essence of Islamic art is that it’s probably the most beautiful and the most diverse art in the world. Each time Islam conquered a new country, Muslims brought their know-how (which at the beginning wasn’t very much) and fused it with that of the country they conquered. For instance, at the time Islam took over Iran, the country was already an empire. It had an abundance of precious metals and it had skilled craftsmen, which the Muslims transformed with their ingenuity to create the art that we see today. The same happened in Egypt, in Tunisia, in Morocco, in Greater Syria. About ten to fifteen years ago, we also saw a flurry of Islamic artefacts coming out of China and Thailand – Chinese Qur’ans, textiles, metalwork, potter – and we realised that Muslims had been there too but did not necessarily make these things. Nevertheless, they left their influence there.

In the 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Africans didn’t have or produce any Islamic arts, because, wealth-wise, they were not in a position to do so. Not many people are aware that 47% of the African population is Muslim. Some were converted in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, others are second, third, or even fourth generation Muslims. Not all the 54 Muslim countries produced art which was Islamic. To put it simply, the definition of Islamic art is: art produced by Muslim artists for Muslim patrons. If the wealth and patronage were there, the arts flourished.

Q: In this context, do you buy Islamic art that’s produced by Islamic artists for Islamic patrons today?

DK: Contemporary Islamic art is a relatively new phenomenon – it has been in existence no more than eight years, with the exception of Iran, where it has been established for a quarter of a century or so. In the other Muslim countries, the majority of contemporary Islamic art is inspired by the art of the past.

When we exhibited Islamic art in Abu Dhabi, many contemporary artists came to our seminars and asked me afterwards if I would mind if they copied some of the works. When I re-visited a year later, I saw one of the 18th century Moroccan tapestries in my collection (blue silk with the name of Allah embroidered in silver) had been copied onto a black canvas, with the name of Allah in white ink across it, a bit like putting a topping of cream on a cake. When I asked the artist the price, he said it had been sold for $800,000. Yet, about 25 to 30 years ago, I had paid a fraction of that for the original.

Porcelain painted in underglaze blue

Height 60.5 cm

Signed Makuzu Kozan sei (made by Makoza Kozan)

Made by the Miyagawa Kozan Workshop

Unfortunately not many people bother to educate themselves about what is real: the art that has withstood the test of time, whether Islamic, Japanese or any other. I don’t especially mind, because copying is the best critique. It represents a very different skill. The buyer does not necessarily know the object’s history and does not, therefore, think in terms of buying a reproduction. The artist, on the other hand, might say he or she was inspired by the original piece and produced this work as a testimony to that inspiration and as a tribute to his or her love for the art which they had encountered. If people copy your ideas, or the way that you behave in life, it’s a compliment.

Q: Do you think people today have lost their appreciation for well-executed representational art, with conceptual art gaining in importance as a result?

DK: No, I don’t think that is the main reason behind it. I think we’re living in a quick-fix generation: everybody wants to be famous in twenty minutes and everybody wants to be a billionaire overnight. Everything that’s happening around them is quick and the art that’s produced is a reflection of the society we live in. Many of the things that you see by contemporary artists are produced in ten minutes, in a basement somewhere on an assembly line.

Probably 70% of contemporary art collectors, unfortunately, don’t bother to do their homework. I’m not talking about modern art. Modern art is different, it is well established.

Too many contemporary art buyers hire an advisor because all they are interested in is to buying an asset that will appreciate rather than in buying the work of art itself. They buy something for £10,000 so they can say to their friends, ‘you know, I bought at £10,000 a few months ago, now it’s worth £25,000’. It’s becoming more or less and more a game of commodity and asset appreciation, and making money. The majority of the people who are acquiring these things are not really lovers of art and culture.

I spoke to someone who was buying contemporary art by groups and numbers, like 50 to 60 artists. I said to them, ‘What are you doing? Do you love what you buy?’ He replied ’No, it’s very much like investing in different hi-tech companies. We buy 50, 60 artists – if one of them turns out to be famous, it pays for the rest.’ That’s the attitude of some of these people.

Q: You are saying that it’s quite rare to come across collectors who have a finely tuned and developed sense of aesthetics.

Torna district, south-west Scania

Circa 1800

52 x 115 cm, dove-tail tapestry

DK: The problem is that the word ‘collector’ is being used very loosely today. Being a collector is an incredible responsibility. You could call yourself a collector, but you are only a true collector only if you fulfil five criteria: you have to acquire, you have to conserve, you have to research, you have to publish and you have to exhibit. Once you fulfil these five criteria, it means that you are doing something for humanity, not just for yourself.

You have people who buy a couple of paintings – say, one Picasso and one other work of art work – put them in the dining room and think, ‘I’m a collector’. In fact, they are a selector for their own pleasure. That’s a different story. The word ‘collector’ should be a sacred one. You cannot call just anyone a collector. You have to look at what that collector has done for everyone else because at the end of the day, nothing belongs to us. We are only temporary custodians of everything that we own. From the time that we are born, we start borrowing from the universe. We borrow the air, we borrow the car, we borrow the plants, we borrow the house, we borrow the art, everything that we take, we borrow. It doesn’t belong to us.

Q: What of collectors who own massive collections that are never exhibited?

DK: That’s the difference between collectors and hoarders. They are hoarders and what they do, as far as I’m concerned, is unfair to the soul of the artists. The collector has a responsibility to exhibit the artists’ works.

When I go to some of my exhibitions, I have to give a speech afterwards. Usually somebody will introduce me – the director of the museum or an academic or an ex-politician – as the collector/owner of the collection. What they do is they read something about you and they start praising you. I say to them, ‘We are not here tonight to praise me at all. What I ask you to do – I beg you to do – is to go and see the exhibition and keep your praises for the souls of the artists who produced these magnificent objects. At the end of the day we, the collectors, are only vehicles through which these things are amassed, given a life, and secured for posterity.

That’s all a real collector does because our life on this planet, compared to the life of some of these works, is a drop in the ocean. Some of these objects were produced 800, 1,000, 2,000 years ago.

People today are becoming lazy, nobody wants to go to a museum and learn. They don’t follow their passion. Life without a passion is like fire without a flame. Collecting is about dreaming, planning and pursuing, but not for yourself. You have to understand that you must share that dream with others – it’s like having all the love in the world, but if you don’t express it, it’s as if you don’t have it.

Q: Do you not think that the very perception of what art is has changed in the last twenty years or so?

DK: I think, less, probably ten to fifteen years. You go to a gallery or a museum today and you see a pack of rice on the floor and they tell you, ‘this is art’. If something requires an explanation, in my view it is not art but an idea. Some contemporary artists (not all) claim credit for it because they came up with the idea first. They are, in fact, exhibiting an idea in the place of art.

Silver, with shakado, shibuichi, gold, malachite, coral, tiger’s-eye, agate and nephrite; crystal ball

Height 37.1 cm

Signed Shoami Katsuyoshi sen (carved by Shoami Katsuyoshi)

By Shoami Katsuyoshi (1832-1908)

Compare this with the craftsmanship of centuries ago, when it took twenty years and six to seven artists to produce one piece. Some contemporary art will withstand the test of time but it is too soon to judge it now because every day, there are a couple of thousand new artists popping up all over the world.

Q: Aside from your collections, what is the thing you most treasure in life?

DK: It doesn’t matter how successful you are in your collecting life, you have to put your family first and put the collection around it, not the other way round. Because the most treasured thing for anybody is their family, their children and their friends. I mean genuine friends, because if you are successful, people will come to you. Some will use your kindness and turn their back. It’s the human condition but it’s much better to be a good-hearted person and be hurt than to be a nasty person. I’ve lived by this rule all my life and have been able to achieve what I have through honesty. I wouldn’t want to change how I’ve lived.

Q: Which artist, living or dead, would you most like to have to known and why?

DK: If you have children and someone asks you, ‘which one is your favourite?’, would you find it easy to answer?

Q: What advice would you give to someone who is quite passionate about art but has a very limited budget?

DK: There are always ways of spending your money. Before you start, go and visit as many museums as you can. Find what pleases you because if you look at something and all of a sudden get butterflies in your stomach, they start fluttering flying. It’s rather like falling in love with a woman. Then see if you could afford to start collecting that at all. If you can’t, find something that you can afford and very gently start buying under the radar. Not publicly, because once people find out what area interests you, obviously they would compete with you. So find a niche that you think has potential, but be true to your passion and your love. Don’t follow the money because collecting is not about money – the minute you bring money into it, you lose sight of the passion.

Q: You’re the founder of the Maimonides Foundation which has very admirable aims. Do you encounter resistance towards its work amongst entrenched fundamentalists, whether Jewish, Christian or Islamic?

DK: I think more and more people realise that there is far more that unites the three religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – than divides them.

One of the things that we are doing is going to elementary schools and teaching children between the ages of eight and ten that there is very little difference between these three religions. If you succeed in getting them to form an opinion at a young age, then in ten, fifteen, twenty years, we would have a new society. If you don’t reach them then, they go and meet other people and they think that the Christians are no good or the Jews are no good or the police are no good, without even knowing why.

That is why we have launched the Interfaith Explorer programme – there are more than 400 videos on it. It was an idea that we came up with, so I went to a few schools for a demonstration before we launched our website. I said, ‘why don’t you get a basket of lemons, let’s say about 24 lemons for 24 students, mix them up, and ask everyone to pick a lemon. Ask them to study their lemon, make sure that they become familiar with it and recognise it, then put it back in the basket. We shake the basket and everyone goes back and finds their lemon’. Some of the lemons were small, others large; some had a spot or some other distinguishing mark but in the end, a lemon is a lemon. It is the same with religion – the three main religions fall in the same category. It’s a concept that’s easy for children to understand. We have no choice but to start now. If we don’t, in twenty to thirty years we’ll be sitting down here having the same conversation about the Middle East problem. That is why I’m now exporting these ideas now. I’m talking to a lot of countries. I’m hoping to go to the United Nations and get the attention of UNESCO so that we can find a way forward.

Q: What would you say to any detractors?

DK: What I have done is for the sake of humanity. I have assembled the largest collection of Islamic art and safeguarded it for our cousins – the Muslims refer to me as the ‘cultural ambassador of Islam’.

As for detractors, I always remember something that my late father, God bless his soul, told me when I was a child. He said, ‘Son, when you’re a little bird in the middle of a forest, sitting on a beautiful branch, if there are a hundred passers-by who decide that they’re going to get you and throw a hundred stones at you, one of them may hit you. When you become an elephant walking in the forest, if they throw a hundred stones at you, fifty of them will hit you. But the advantage is that by the time you are so big and powerful that doesn’t matter’.

It’s good to question yourself from time to time. When I look back at my life and all the things I’ve done, I marvel at it. But the reason I talk about it is that for the young generation it’s important to see that everything is possible – to see that if they have a dream and if they pursue and plan that dream, they’ll get there. Because dreaming on its own doesn’t get you anywhere

A week after this interview took place, on 16 October Professor Khalili was named UNESCO’s newest Goodwill Ambassador for the promotion of peace among nations through culture and education.

Khalili had addressed the UN on the 21 September in his characteristic allegorical style, stating his belief that ‘the real weapon of mass destruction is ignorance’ and that its solution, therefore, should be education. When we talked to him, on the eve of his investiture as Goodwill Ambassador, he spoke about his conviction that sustainable peace can be achieved through culture.

In his lifetime, he has done more than any other individual to develop an appreciation for Islamic art throughout the world. One hopes that under his tenure the Muslim world will do even more to celebrate and honour its amazing and hugely diverse art heritage.

It is perhaps fitting to end this feature with Khalili’s favourite Persian poem, one he considers to be a ‘guiding message for humanity’:

‘Each tinted fragment sparkles in the sun

A Thousand colours but the light is one’

*Nasser David Khalili has assembled, under the auspices of the Khalili Family Trust, five comprehensive art collections, together comprising some 25,000 works, including The Arts of the Islamic World, 700-2000; Japanese Art of the Meiji Period, 1868-1912; Swedish Textiles, 1700-1900; Spanish Damascened Metalwork, 1850-1900; and Enamels of the World, 1700-2000. The Khalili Collections are fully represented in a series of over 40 volumes, of which 90% has already been published.

**Khalili has also made several contributions to the scholarship of Islamic art, endowed a chair devoted to the decorative arts of Islam at SOAS and supported research fellowships at Oxford University. The Khalili Research Centre for the Art and Material Culture of the Middle East opened in 2005.

***The Maimonides Foundation is a charity which promotes peace and understanding between the three great monotheistic faiths: Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Saving...

Saving...